[RH] мқҢм•…кіј мҲҳл©ҙмқҳ кҙҖкі„

лҢҖл¶Җ분 мӮ¬лһҢл“ӨмқҖ н•ҳлЈЁ мў…мқј мқҢм•…мқ„ л“Јкі , мў…мў… м·Ём№Ё мӢңк°„м—җлҸ„ кёҙмһҘмқ„ н’Җкё° мң„н•ҙ мқҢм•…мқ„ л“ЈлҠ”лӢӨ. к·ёлҹ¬лӮҳ мқҙ н–үмң„к°Җ мӢӨм ңлЎң мҲҳл©ҙмқ„ л°©н•ҙн•ҳлҠ” кІғмқҖ м•„лӢҗк№Ң? лҜёкөӯ лІ мқјлҹ¬ лҢҖн•ҷкөҗ(Baylor University) мҲҳл©ҙ м—°кө¬нҢҖмқҖ мқҢм•…, нҠ№нһҲ вҖҳмһҗмӢ мқҳ л§ҲмқҢм—җ л§ҙлҸ„лҠ”вҖҷ л…ёлһҳк°Җ мҲҳл©ҙ нҢЁн„ҙм—җ м–ҙл–Ө мҳҒн–Ҙмқ„ лҜём№ мҲҳ мһҲлҠ”м§ҖлҘј мЎ°мӮ¬н–ҲлӢӨ.

вҖҳмӮ¬мқҙмҪңлЎңм§Җ컬 мӮ¬мқҙм–ёмҠӨ(Psychological Science)вҖҷ м Җл„җм—җ л°ңн‘ңлҗң мқҙ м—°кө¬лҠ” мқҢм•… к°җмғҒкіј мҲҳл©ҙ мӮ¬мқҙмқҳ кҙҖкі„лҘј мЎ°мӮ¬н–Ҳкі , мқҙлҠ” кұ°мқҳ нғҗкө¬лҗҳм§Җ м•ҠмқҖ л©”м»ӨлӢҲмҰҳмқё мқҙм–ҙмӣң(ear-worm) нҳ„мғҒ, мҰү к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмңјлЎң л¶ҲлҰ¬лҠ” 비мһҗл°ңм Ғ нҳ№мқҖ л¬ҙмқҳмӢқм Ғ мқҢм•… мқҙлҜём§Җм—җ мҙҲм җмқ„ л§һм·„лӢӨ. мқҙ к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмқҖ мқјл°ҳм ҒмңјлЎң к№Ём–ҙ мһҲлҠ” лҸҷм•Ҳ л°ңмғқн•ҳм§Җл§Ң м—°кө¬мһҗл“ӨмқҖ мҲҳл©ҙ мӨ‘м—җлҸ„ л°ңмғқн• мҲҳ мһҲмқҢмқ„ л°ңкІ¬н–ҲлӢӨ.

мҡ°лҰ¬ л‘җлҮҢлҠ” мҲҳл©ҙ мӨ‘м—җ мһҲмқ„ л•ҢлҘј нҸ¬н•Ён•ҳм—¬ м–ҙл–Ө кІғлҸ„ мһ¬мғқлҗҳм§Җ м•Ҡмқ„ л•ҢмЎ°м°ЁлҸ„ мқҢм•…мқ„ кі„мҶҚ мІҳлҰ¬н•ңлӢӨ. мқҢм•…мқ„ л“Өмңјл©ҙ 기분мқҙ мўӢлӢӨлҠ” кІғмқҖ лҲ„кө¬лӮҳ м•Ңкі мһҲлӢӨ. к·ёлһҳм„ңмқём§Җ мІӯмҶҢл…„кіј мІӯл…„л“ӨмқҖ мқјмғҒм ҒмңјлЎң м·Ём№Ё мӢңк°„м—җ мқҢм•…мқ„ л“ЈлҠ”лӢӨ. к·ёлҹ¬лӮҳ мқҢм•…мқ„ л§Һмқҙ л“Өмқ„мҲҳлЎқ м·Ём№Ё мӢңк°„м—җлҸ„ мӮ¬лқјм§Җм§Җ м•ҠлҠ” к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒм—җ л…ём¶ңлҗ нҷ•лҘ мқҙ лҶ’아진лӢӨ. к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмқҙ л°ңмғқн•ҳл©ҙ мҲҷл©ҙмқ„ м·Ён• мҲҳк°Җ м—ҶлӢӨ.

к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмқ„ м Җл…Ғм—җ к·ңм№ҷм ҒмңјлЎң, мҳҲлҘј л“Өм–ҙ мқјмЈјмқјм—җ н•ң лІҲ мқҙмғҒ кІҪн—ҳн•ҳлҠ” мӮ¬лһҢл“ӨмқҖ к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмқ„ кұ°мқҳ кІҪн—ҳн•ҳм§Җ м•ҠлҠ” мӮ¬лһҢл“Өм—җ 비н•ҙ мҲҳл©ҙмқҳ м§Ҳмқҙ мўӢм§Җ м•Ҡмқ„ к°ҖлҠҘм„ұмқҙ 6л°°лӮҳ лҚ” лҶ’лӢӨ. лҶҖлһҚкІҢлҸ„ мқҙ м—°кө¬м—җ л”°лҘҙл©ҙ мқјл¶Җ кё°м•…, мҰү м•…кё°л§ҢмңјлЎң м—°мЈјлҗҳлҠ” мқҢм•…мқҙ м—ҙм •м Ғмқё мқҢм•…ліҙлӢӨ к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмқ„ мң л°ңн•ҳкі , мҲҳл©ҙмқҳ м§Ҳмқ„ л°©н•ҙн• к°ҖлҠҘм„ұмқҙ лҚ” лҶ’мқҖ кІғмңјлЎң лӮҳнғҖлӮ¬лӢӨ.

мқҙ м—°кө¬лҠ” м„Өл¬ё мЎ°мӮ¬мҷҖ м—°кө¬мӢӨ мӢӨн—ҳмқҙ н•Ёк»ҳ 진н–үлҗң кІғмқҙлӢӨ. м„Өл¬ёмЎ°мӮ¬лҠ” мҲҳл©ҙмқҳ м§Ҳ, мқҢм•… мІӯм·Ё мҠөкҙҖ, к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ л№ҲлҸ„м—җ лҢҖн•ң мқјл Ёмқҳ мЎ°мӮ¬лҘј мҷ„лЈҢн•ң 209лӘ…мқҳ м°ёк°ҖмһҗлҘј лҢҖмғҒмңјлЎң 진н–үлҗҳм—Ҳкі , м—¬кё°м—җлҠ” мһ л“Өл Ө мӢңлҸ„н• л•Ң, н•ңл°ӨмӨ‘м—җ к№Ёкұ°лӮҳ, м•„м№Ём—җ мһ м—җм„ң к№Ёмһҗл§Ҳмһҗ к·Җ лІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмқ„ кІҪн—ҳн•ң л№ҲлҸ„к°Җ нҸ¬н•Ёлҗҳм—ҲлӢӨ.

м—°кө¬мӢӨ мӢӨн—ҳм—җлҠ” 50лӘ…мқҙ м°ёк°Җн–ҲлҠ”лҚ°, лІ мқјлҹ¬ лҢҖн•ҷкөҗ мҲҳл©ҙ мӢ кІҪ кіјн•ҷ мқём§Җ м—°кө¬мҶҢм—җм„ң 진н–үлҗҳм—ҲлӢӨ. мқҙкіім—җм„ң м—°кө¬нҢҖмқҖ к·ҖлІҢл Ҳк°Җ мҲҳл©ҙмқҳ м§Ҳм—җ м–ҙл–Ө мҳҒн–Ҙмқ„ лҜём№ҳлҠ”м§Җ м•Ңм•„ліҙкё° мң„н•ҙ к·ҖлІҢл ҲлҘј мң лҸ„н•ҳл Ө мӢңлҸ„н–ҲлӢӨ. мҲҳл©ҙмқҳ мқјл°ҳ н‘ңмӨҖ мёЎм • л°©мӢқмқё вҖҳмҲҳл©ҙлӢӨмӣҗкІҖмӮ¬вҖҷлҠ” мҲҳл©ҙ мӨ‘мқё м°ёк°Җмһҗмқҳ лҮҢнҢҢ, мӢ¬л°•мҲҳ, нҳёнқЎ л“ұмқ„ кё°лЎқн•ҳлҠ” лҚ° мӮ¬мҡ©лҗҳм—ҲлӢӨ.

м·Ём№Ё м „ м—°кө¬нҢҖмқҖ лҢҖмӨ‘ мқёкё°кіЎмқё н…Ңмқјлҹ¬ мҠӨмң„н”„нҠё(Taylor Swift)мқҳ вҖҳмүҗмқҙнҒ¬ мһҮ мҳӨн”„(Shake It Off)вҖҷ, м№јлҰ¬ л Ҳмқҙ м ӯмҠЁ(Carly Rae Jepsen)мқҳ вҖҳмҪң лҜё л©”мқҙ비(Call Me Maybe), м ҖлӢҲ(Journey)мқҳ вҖҷлҸҲ мҠӨнғ‘ л№ҢлҰ¬л№Ҳ(Don't Stop Believin)вҖҳмқ„ л“Өл ӨмӨ¬лӢӨ. мқҙнӣ„ мӢӨн—ҳ м°ёк°ҖмһҗлҘј л¬ҙмһ‘мң„лЎң м§Җм •н•ҳм—¬ н•ҙлӢ№ л…ёлһҳмқҳ мӣҗліё лІ„м „мқҙлӮҳ к°ҖмӮ¬к°Җ м—ҶлҠ” кё°м•… лІ„м „мқ„ л“ЈкІҢ н–ҲлӢӨ. м°ёк°Җмһҗл“ӨмқҖ к·ҖлІҢл ҲлҘј кІҪн—ҳн–ҲлҠ”м§ҖмҷҖ к·ё л°ңмғқ мӢңкё°м—җ мқ‘лӢөн–Ҳкі , мқҙнӣ„ м—°кө¬нҢҖмқҖ мқҙкІғмқҙ м•јк°„ мҲҳл©ҙ мғқлҰ¬м—җ м–ҙл–Ө мҳҒн–Ҙмқ„ лҜём№ҳлҠ”м§Җ 분м„қн–ҲлӢӨ. кІ°кіјм ҒмңјлЎң, к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмқҙ мқјм–ҙлӮң мӮ¬лһҢл“ӨмқҖ мһ л“Өкё°к°Җ лҚ” м–ҙл өкі л°Өм—җ к№ЁлҠ” кІҪмҡ°к°Җ лҚ” л§Һм•ҳмңјл©° мҲҳл©ҙмқҳ к°ҖлІјмҡҙ лӢЁкі„м—җ лЁёл¬ҙлҘҙлҠ” мӢңк°„мқҙ лҚ” л§Һм•ҳлӢӨ.

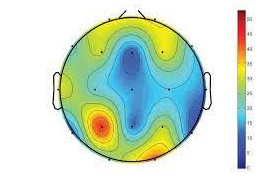

лҳҗн•ң м—°кө¬мӢӨ мӢӨн—ҳм—җм„ңлҠ” лҮҢмқҳ м „кё°м Ғ нҷңлҸҷмқ„ м •лҹүм ҒмңјлЎң 분м„қн•ҳм—¬ мҲҳл©ҙ мқҳмЎҙм Ғ кё°м–ө к°•нҷ”мқҳ мғқлҰ¬н•ҷм Ғ м§Җн‘ңлҘј мЎ°мӮ¬н–ҲлӢӨ. кё°м–ө нҶөн•©мқҖ мһ мһҗлҠ” лҸҷм•Ҳ мқјмӢңм Ғ кё°м–өмқҙ мһҗл°ңм ҒмңјлЎң мһ¬нҷңм„ұнҷ”лҗҳм–ҙ ліҙлӢӨ мһҘкё°м Ғ нҳ•нғңлЎң ліҖнҳ•лҗҳлҠ” кіјм •мқҙлӢӨ.

м—°кө¬нҢҖмқҖ мӮ¬лһҢл“Өмқҙ мһ л“Өл Ө н•ҳлҠ” м·Ём№Ё мӢңк°„м—җ к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмқҙ л°ңмғқн• кІғмқҙлқјкі к°Җм •н–Ҳм§Җл§Ң, мӢӨм ңлЎң мӢӨн—ҳ м°ёк°Җмһҗл“ӨмқҖ к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмңјлЎң к·ңм№ҷм ҒмңјлЎң мһ м—җм„ң к№Ём–ҙлӮңлӢӨкі мқҙм•јкё°н–ҲлӢӨ. к·ёлҰ¬кі мқҙ кІ°кіјлҠ” м„Өл¬ё мЎ°мӮ¬мҷҖ м—°кө¬мӢӨ мӢӨн—ҳ лӘЁл‘җм—җм„ң л°ңкІ¬лҗҳм—ҲлӢӨ. лҳҗн•ң мҲҳл©ҙ к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒм—җ л…ём¶ңлҗң мӢӨн—ҳ м°ёк°ҖмһҗлҠ” кё°м–ө мһ¬нҷңм„ұнҷ”мқҳ м§Җн‘ңмқё вҖҷмҲҳл©ҙ мӨ‘ лҚ” лҠҗлҰ° 진лҸҷвҖҳ нҳ„мғҒмқ„ ліҙмҳҖлҠ”лҚ°, мқҙлҹ¬н•ң лҠҗлҰ° 진лҸҷмқҳ мҰқк°ҖлҠ” мӮ¬лһҢл“Өмқҙ к№Ём–ҙ мһҲмқ„ л•Ң к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ мІҳлҰ¬мҷҖ кҙҖл Ёлҗң мқјм°Ё мІӯк°Ғ н”јм§Ҳм—җ н•ҙлӢ№н•ҳлҠ” мҳҒм—ӯм—җм„ң м§Җл°°м Ғмқҙм—ҲлӢӨ.

мқҙкІғмқҖ м •л§җ лҶҖлқјмҡҙ мқјмқҙм§Җ м•ҠмқҖк°Җ! кұ°мқҳ лӘЁл“ мӮ¬лһҢл“Өмқҙ мқҢм•…мқҙ мҲҳл©ҙмқ„ к°ңм„ н•ңлӢӨкі мғқк°Ғн•ҳм§Җл§Ң мқҙ м—°кө¬лҘј нҶөн•ҙ мқҢм•…мқ„ лҚ” л§Һмқҙ л“ЈлҠ” мӮ¬лһҢл“Өмқҳ мҲҳл©ҙмқҳ м§Ҳмқҙ лҚ” м•Ҳ мўӢмқҖ кІғмңјлЎң лӮҳнғҖлӮң кІғмқҙлӢӨ. м •л§җ лҶҖлқјмҡҙ кІғмқҖ кё°м•…мқҙ мҲҳл©ҙмқҳ м§Ҳмқ„ лҚ” м•…нҷ”мӢңнӮЁлӢӨлҠ” кІғмқҙлӢӨ. кё°м•…мқҖ к·ҖлІҢл ҲлҘј м•Ҫ 2л°° лҚ” л§Һмқҙ л°ңмғқмӢңнӮЁлӢӨ.

м—°кө¬м—җ л”°лҘҙл©ҙ к°ҖмһҘ к·№лӢЁм Ғмқё мқҢм•… мІӯм·Ё мҠөкҙҖмқ„ к°Җ진 мӮ¬лһҢл“ӨмқҖ м§ҖмҶҚм Ғмқё к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒкіј мҲҳл©ҙмқҳ м§Ҳ м Җн•ҳлҘј кІҪн—ҳн–ҲлӢӨ. мқҙлҹ¬н•ң кІ°кіјлҠ” мқҢм•…мқҙ мҲҳл©ҙм—җ лҸ„мӣҖмқҙ лҗ мҲҳ мһҲлҠ” мөңл©ҙ лҸ„кө¬лқјлҠ” мғқк°Ғкіј лӘЁмҲңлҗңлӢӨ. мҳӨлҠҳлӮ мқҳлЈҢ кё°кҙҖмқҖ мқјл°ҳм ҒмңјлЎң мһҗкё° м „м—җ мЎ°мҡ©н•ң мқҢм•…мқ„ л“Өмқ„ кІғмқ„ к¶ҢмһҘн•ңлӢӨ. к·ёлҹ¬лӮҳ лІ мқјлҹ¬ лҢҖн•ҷ м—°кө¬нҢҖмқҖ вҖҷмқҢм•…мқҙ л©Ҳм¶ҳ нӣ„м—җлҸ„ мһ мһҗлҠ” лҮҢк°Җ лӘҮ мӢңк°„ лҸҷм•Ҳ мқҢм•…мқ„ кі„мҶҚ мІҳлҰ¬н•ңлӢӨвҖҳлҠ” кІғмқ„ к°қкҙҖм ҒмңјлЎң л°қнҳҖлғҲлӢӨ.

к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмқҖ мҲҳл©ҙм—җ л¶Җм •м Ғ мҳҒн–Ҙмқ„ лҜём№ҳкё° л•Ңл¬ём—җ, к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмңјлЎң мқён•ҙ мҲҳл©ҙм—җ л°©н•ҙлҘј л°ӣлҠ” кІҪмҡ° к°ҖлҒ” нңҙмӢқмқ„ м·Ён•ҳлҠ” кІғмқҙ мўӢлӢӨ. мқҢм•…мқҳ нғҖмқҙл°ҚлҸ„ мӨ‘мҡ”н•ҳлӢӨ. м·Ём№Ё м „м—җлҠ” н”јн•ҳлҠ” кІғмқҙ мўӢлӢӨ.

к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмқ„ мҷ„нҷ”мӢңнӮӨлҠ” лҳҗ лӢӨлҘё л°©лІ•мқҖ мқём§Җ нҷңлҸҷмқ„ н•ҳлҠ” кІғмқҙлӢӨ. мһ‘м—…, л¬ём ң лҳҗлҠ” м–ҙл–Ө нҷңлҸҷм—җ мҷ„м „нһҲ 집мӨ‘н•ҳл©ҙ к·ҖлІҢл Ҳ нҳ„мғҒмңјлЎңл¶Җн„° лҮҢлҘј мӮ°л§Ңн•ҳкІҢ н•ҳлҠ” лҚ° лҸ„мӣҖмқҙ лҗңлӢӨ. м·Ём№Ё мӢңк°„м—җ TVлҘј ліҙкұ°лӮҳ 비디мҳӨ кІҢмһ„мқ„ н•ҳлҠ” кІғкіј к°ҷмқҙ нһҳл“ нҷңлҸҷмқҙлӮҳ мҲҳл©ҙмқ„ л°©н•ҙн•ҳлҠ” нҷңлҸҷліҙлӢӨлҠ”, н• мқј лӘ©лЎқмқ„ мһ‘м„ұн•ҳкі мғқк°Ғмқ„ мў…мқҙм—җ м ҒлҠ” лҚ° 5~10분мқ„ н• м• н• кІғмқ„ м—°кө¬нҢҖмқҖ м ңм•Ҳн•ҳкі мһҲлӢӨ.

м—°кө¬нҢҖмқҳ мқҙм „ м—°кө¬м—җ л”°лҘҙл©ҙ, мһ л“Өкё° м „ 5분 лҸҷм•Ҳ м•һмңјлЎң н•ҙм•ј н• мһ‘м—…мқ„ мғқк°Ғн•ҳкұ°лӮҳ м ҒлҠ” м°ёк°Җмһҗл“ӨмқҖ мқҙ мһ‘м—…м—җ лҢҖн•ң л¶Ҳм•Ҳн•ң л§ҲмқҢм—җм„ң лІ—м–ҙлӮҳ, лҚ” л№ЁлҰ¬ мһ мқ„ мһҳ мҲҳ мһҲм—ҲлӢӨ.

- PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE, June 9, 2021, вҖңBedtime Music, Involuntary Musical Imag- ery, and Sleep,вҖқ by Michael K. Scullin, Chenlu

Gao, Paul Fillmore. © 2021 by Association for Psychological Science. All rights reserved.

To view or purchase this article, please visit:

[RH] Bedtime Music, Involuntary Musical Imagery, and Sleep

Most people listen to music throughout their day and often near bedtime to wind down. But can that actually cause your sleep to suffer? Sleep researchers at Baylor University studies how music - and particularly songs that get вҖңstuck in your mindвҖқ - might affect sleep patterns.

The recent study published in the journal Psychological Science, investigated the relationship between music listening and sleep, focusing on a rarely explored mechanism: involuntary musical imagery, called вҖңear-worms,вҖқ when a song or tune replays over and over in a personвҖҷs mind. These commonly happen while awake, but the researchers found that they also can happen while trying to sleep.

Our brains continue to process music even when none is playing, including apparently while we are asleep. Everyone knows that music listening feels good. Adolescents and young adults routinely listen to music near bedtime. But sometimes you can have too much of a good thing. The more you listen to music, the more likely you are to catch an ear-worm that wonвҖҷt go away at bedtime. When that happens, chances are your sleep is going to suffer.

People who experience these so-called вҖңear-wormsвҖқ regularly at night - one or more times per week - are six times as likely to have poor sleep quality compared to people who rarely experience earworms. Surprisingly, the study found that some instrumental music is more likely to lead to earworms and disrupt sleep quality than lyrical music.

The study involved a survey and a laboratory experiment. The survey involved 209 participants who completed a series of surveys on sleep quality, music listening habits and ear-worm frequency, including how often they experienced an earworm while trying to fall asleep, waking up in the middle of the night and immediately upon waking in the morning.

In the experimental study, fifty participants were brought into the Sleep Neuroscience and Cognition Laboratory at Baylor, where the research team attempted to induce earworms to determine how it affected sleep quality. Polysomnography - a comprehensive test which is the gold standard measurement for sleep - was used to record the participantsвҖҷ brain waves, heart rate, breathing and more while they slept.

Before bedtime, the researchers played three popular and catchy songs - Taylor SwiftвҖҷs вҖҳShake It Off,вҖҷ Carly Rae JepsenвҖҷs вҖҳCall Me MaybeвҖҷ and JourneyвҖҷs вҖҳDonвҖҷt Stop BelievinвҖҷ. Then, they randomly assigned participants to listen to the original versions of those songs or the de-lyricized instrumental versions of the songs. Participants responded whether and when they experienced an earworm. Then the researchers analyzed whether that impacted their nighttime sleep physiology. People who caught an earworm had greater difficulty falling asleep, more nighttime awakenings, and spent more time in light stages of sleep.вҖқ

Additionally, electrical activity in the brain from the experimental study was quantitatively analyzed to examine physiological markers of sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Memory consolidation is the process by which temporary memories are spontaneously reactivated during sleep and trans- formed into a more long-term form.

The researchers thought that people would have earworms at bedtime when they were trying to fall asleep, but they certainly didnвҖҷt know that people would report regularly waking up from sleep with an earworm. But they saw that in both the survey and experimental study.

Participants who had a sleep earworm showed more slow oscillations during sleep, a marker of memory reactivation. The increase in slow oscillations was dominant over the region corresponding to the primary auditory cortex which is implicated in earworm processing when people are awake.

This was a real surprise? Almost everyone thinks music improves their sleep, but this research found those who listened to more music slept worse. What was really surprising was that instrumental music led to worse sleep quality - instrumental music leads to about twice as many earworms.

The study found that individuals with the most extreme music listening habits experienced persistent earworms and a decline in sleep quality. These results contradict the idea of music as a tool hypnotic that might help sleep. Today, health organizations commonly recommend listening to quiet music before bed- time; these recommendations largely arise from self-reported studies. The Baylor team has objectively established that the sleeping brain continues to process music for several hours, even after the music stops.

Knowing that earworms negatively affect sleep, the researchers recommend first trying to moderate music listening or taking occasional breaks if bothered by earworms. The timing of music is also important; so, try to avoid it before bed.

If you commonly listening to music while being in bed, then youвҖҷll have an association where being in bed might trigger an earworm even when youвҖҷre not listening to music, such as when youвҖҷre trying to fall asleep.

Another way to get rid of an earworm is to engage in cognitive activity — fully focusing on a task, problem or activity helps to distract your brain from earworms. Near bedtime, rather than engaging in a demanding activity or something that would disrupt your sleep, like watching TV or playing video games, the researchers suggest spending five to 10 minutes writing out a to-do list and putting your thoughts to paper.

This has multiple benefits. A previous study by these researchers found that participants who took five minutes to write down upcoming tasks before bed were able to вҖңoffloadвҖқ those worrying thoughts about the future and that led to faster sleep.

- PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE, June 9, 2021, вҖңBedtime Music, Involuntary Musical Imag- ery, and Sleep,вҖқ by Michael K. Scullin, Chenlu

Gao, Paul Fillmore. © 2021 by Association for Psychological Science. All rights reserved.

To view or purchase this article, please visit: